projects >>

cicadas

ON CICADAS AND CICADA GAMES1

The cicada is a little insect with an outsize song. It starts its life as an egg deposited in a tree branch; it drops to the ground as larvae covered in fake eyes; it tunnels, spending anywhere from one to seventeen years underground2, suckling tree roots and changing shape.

When the soil reaches a certain temperature, it emerges with its siblings as a brown, hunched, six-legged nymph. Together, the brood molt exuviae, the papery brown shells, unfurling fluorescent wings atop glowing bodies. Within a day, the fluorescent colors have faded into dark camouflage. A cicada brood will spend the next 6-8 weeks singing and mating, eventually laying eggs in tree branches right before dropping dead. Cicadas eat very little – tree sap, dew – but until the early 20th century, it was thought that they ate nothing at all, with their entire waking lives spent in song and sex.

Male cicadas sing by resonating their hollowed abdomens; female cicadas respond by clicking their legs. The song of the males is loudest in the bright sun of noon, it quiets with a passing cloud; cicadas sing also for the light of the moon.

The fable of the grasshopper and the ant3 is often told with a cicada replacing the grasshopper, and this pairing unintentionally shifts the “lesson” of the fable. John Golding Myers, in his 1929 INSECT SINGERS: A NATURAL HISTORY OF THE CICADA, also contrasted the ant and the cicada:

John Golding Myers, INSECT SINGERS: A NATURAL HISTORY OF THE CICADA (G. Routledge and Sons, 1929), p. 195

As Myers writes, “the [cicada] adults are devoted wholly to Apollo and to Eros…” (196). Indeed, cicadas are the lushes of the insect world – unlike the grasshopper, they are dead by the end of the summer not because they’ve failed to prepare for winter, but because they’ve sung themselves out. They’ve already played their only game.

Magicicada

I grew up in Eastern Ohio, which is the territory of several 13- and 17-year broods of Magicicada, and so, like many, I can measure out my life with cicada broods.

Since I was a child, I have been horrified and enchanted by the cicadas' emergence (all at once, they are everywhere); their roar (loudest in the direct sun, calmed by a passing cloud, triggered also by the moon); their protruding eyes (“the gibbous / mirrored eye of an insect”); their hollow chambers (an outer membrane vibrates in waves, creating a drone that’s amplified by the empty bodies); and their discarded, translucent exoskeletons, clinging to pine branches with little hollow legs.

HOLLOWED BODIES, RELENTLESS TONGUES

The Greek cicada myth was invented by Socrates in Plato’s Phaedrus. Socrates and Phaedrus wander through the Athenian countryside, debating the art of rhetoric by way of several speeches about romantic love. Listening to the drone of the cicadas, Socrates creates their myth: they were once men who, obsessed with music, sang without ceasing, forgoing food and drink, hollowing themselves out, until they became insects with loud songs emanating from empty centers. Now they do the muses’ bidding: spying on humans and reporting who sleeps at noon and who, virtuously, stays awake. The lively song of the cicadas functions like a dialectic (which Socrates contrasts to rhetoric) as they call, respond, and chatter. Paradoxically, the effect of the song on humans is to lull – as rhetoric does – into an illusion that leads to sleep. Ingeborg Bachmann, in her Phaedrus-inspired 1955 audio play, Die Zikaden, describes the play’s characters – who slowly dissolve into the hum of the cicadas – as verzaubert aber verdammt, a characterisation that continues to feel relevant in our current moment of social media and social isolation.

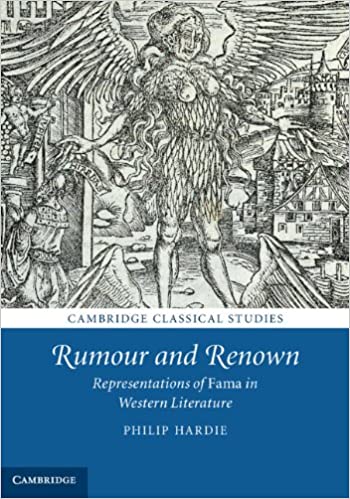

Socrates’ myth of the cicadas derives from a passage in Hesiod’s Works and Days in which Hesiod (in the process of chastising his brother for failing to be industrious and to do honest work) invents a first race of men – a golden people living in paradise, who loved to sing and, singing, slowly dissolved into ghosts. They remain with us still as daemons. With these myths, with the juxtaposition of song and presence, of the loudness of the relentless song and the small size of the singers, of covert surveillance and open debate, I begin to find a link between the cicadas and the Roman goddess Fama (Rumour), whose dimensions are never quite clear – she shrinks and grows, incendiary, cloaked in wagging tongues. Fama, first endowed with her many-tongued, many-eyed form in the Aeneid, was given a home in Ovid’s Metamorphoses: she dwells in a hollow bronze sphere at the center of the whispering gallery that is the Earth, emerging when summoned by other gods, or by gossip. She is the sister of the titans and the last child of angry Earth (Gaia).

Rumour and Renown, by Philip Hardie, is a comprehensive account of the iconography of Fama. The front cover depicts her as first described in Virgil’s Aeneid, covered in tongues. The woodcut image was created in 1502 by Sebastian Brant for the Strassburg edition of the Aeneid.

CICADA GAMES

When I began to write my CICADA GAMES, I was thinking about the emergence and spread of rumour, and the myth that makes cicadas spies for the muses. It seemed to me that cicadas play a single, simple game (emerging, singing, mating, dying), and I began to wonder what would happen if cicadas were indeed called to play a different game entirely, a game of espionage that forced them to inhabit a human-like consciousness.

This was the starting point for an ongoing cycle of cicada poems, which are voiced by a shifting cast of cicada characters. Some poems and poem fragments find the cicada broods idly chattering through riddles and grappling with human memory and emotions.The main CICADA GAME4, which is the first audioplay released in my augmented reality app of the same name, has a complete narrative arc and follows a brood of seven cicadas as they awaken underground and gradually become aware of their status as pawns in a legal dispute between the sun and the muses. The CICADA GAMES utilise the iconography of cicadas and Fama to consider how rhetoric and dialectic function in our society, as the cicada characters grapple with their role in an absurdist surveillance apparatus, with their discovery of human ethics and interiority, and with their desire to play only escapist “cicada games” while being coerced to perform very different missions. ASMR underscores the paradox of the cicadas’ song: ASMR, too, is both a sleep aid and a pathway to a deeper sensory awareness of our surrounding world and of our relations to one another.

-

This essay also appears via Fantom Projects and was published to accompany my appearance on Francesco Cavaliere’s Sussurra Luce radio show in November 2021. ↩︎

-

This differs by genus and species. ↩︎

-

The grasshopper spends the summer lazing about while the ant prepares for winter. ↩︎

-

CICADA GAMES was produced by Czirp Czirp and released in June 2021 in Kongresspark, Vienna. ↩︎